What is Test Driven Development (TDD)?

- 11 mins read

-

By Marjan Venema

- Updated on August 14, 2024

Test Driven Development is a process in which you write the test before you write the code. And when all tests are passing you clean your kitchen: you make the code better.

Yet, Test Driven Development Is Not About Testing

The premise behind test driven development, according to Kent Beck, is that all code should be tested and refactored continually. That sure sounds like it’s about testing, so what gives?

Well, the tests you write in TDD are not the point, but the means.

The point is that by writing tests first and striving to keep them easy to write, you’re doing three important things

You’re creating documentation, living, breathing, never out-of-date specifications (ie documentation).

You’re (re-)designing your code to make and keep it easily testable. And that makes it clean, uncomplicated, and easy to understand and change.

You’re creating a safety net to make changes with confidence.

Benefits of Test Driven Development

In addition to the benefits mentioned in the previous section, TDD also gets you:

Early bug notification

Easy bug diagnosis as the tests pinpoint what went wrong

What it all means for your business, is:

1. It improves your bus factor as knowledge isn’t just in heads and it makes onboarding new hires easier.

2. It lowers the cost of enhancements. Keeping the code clean is also how you minimize the risk of accidental complications. And that means you can maintain a constant pace in delivering value.

3. With the safety net, developers are more willing to merge their changes and pull in other developer’s changes. And, they’ll do it more often. And then trunk based development and continuous integration, delivery, and deployment can really take off.

4. It lowers the number of bugs that ‘escape’ into production and that lowers support costs.

The Surprising Reason to Use TDD

If all those benefits aren’t enough, there’s one more reason to use TDD, one that’ll surprise you.

Kent Beck puts it this way: “Quite simply, test driven development is meant to eliminate fear in application development.”

Fear is good to keep you alive, but it is a killer for work that needs even the slightest bit of cognition.

Uh, What About “Developers Should Not Write the Tests to Test Their Own Code?”

Yes, there are good reasons not to let developers write the tests to test their own code.

However, this advice applies to application level tests.

For developer level tests, getting someone else to write the tests is like hitching the horse behind the wagon.

The requirements usually are several abstraction levels above that of the code needed to implement it. So you need to think through what you need to do and how you’ll do it. Writing the tests first is an excellent, and efficient, way to do that.

And, remember, TDD is not about testing.

And Where Does Test Driven Development Fit in Agile?

Back in 1996, the C3 project team at Chrysler practiced test-first programming. “We always write unit tests before releasing any code, usually before even writing the code.” says the case study on the project titled “Chrysler Goes to “Extremes”.

Writing tests first was just one of the practices used by the C3 team. Taken together, these practices became known as eXtreme programming. Three members of that team, Kent Beck, Martin Fowler, and Ron Jeffries, were among the people that wrote and first signed the Agile Manifesto.

Test driven development is a core Agile practice. It directly supports the Agile value of “Working software over comprehensive documentation”. And does so by protecting working software with tests and creating the documentation as a natural by-product.

How Do You Practice TDD?

Src: Spec-india.com

Test driven development is deceptively simple. Easy to explain what you do when, but not so easy to actually do it. More on why that is, in the following section. First, let’s explain what you do in TDD.

The Cycle and Stages of TDD

Test driven development means going through three phases. Again and again and again.

* Red phase: write a test.

* Green phase: make the test pass by writing the code it guards.

* Blue phase: refactor.

That’s it? Yes, that’s it. But wait, there’s more.

The Rules of TDD As Laid Down by Uncle Bob

Uncle Bob (Robert C. Martin) set out the rules of TDD in chapter 5 Test Driven Development of his book The Clean Coder.

1. You are not allowed to write any production code unless it is to make a failing unit test pass.

2. You are not allowed to write any more of a unit test than is sufficient to fail; and compilation failures are failures.

3. You are not allowed to write any more production code than is sufficient to pass the one failing unit test.

Why follow these rules? Because they’re intended to make your life easier.

But I’m not happy with rule #2. Because treating compilation errors as failures can mask the fact that a test doesn’t have assertions. And that’s bad, because it can fool you into thinking a test is passing when the code is (partly) unwritten or plain wrong.

That said, the intention of the rules is to keep things focused in each phase and to keep you from going down rabbit holes. From experience, that helps a lot in keeping things straight in your head. So:

1. During the red phase (writing the test), only work on test code. A failing test is good. At least if it is the one you’re working on. All others should be green.

2. During the green phase (making the test pass), only work on production code that will make the test pass and don’t refactor anything. If the test you just wrote fails, it means your implementation needs work. If other tests fail, you broke existing functionality and need to backtrack.

3. During the blue phase (refactoring), only refactor production code and don’t make any functional changes. Any failing test means you broke existing functionality. You either haven’t completed the refactoring, or need to backtrack.

Sometimes you’ll find opportunities to refactor test code. For example when you have a bunch of separate [Fact] tests in xUnit that only differ in the arguments they pass to the method under test. You can replace these with a single [Theory] test.

My advice: don’t refactor, but add the theory and when that is in agreement with the facts, you can remove the facts.

Example of Using TDD

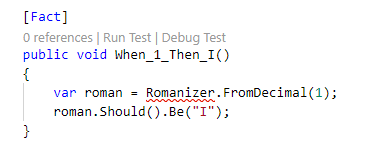

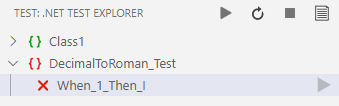

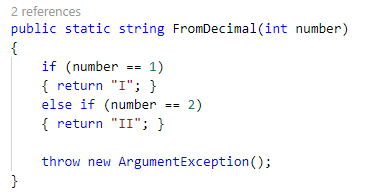

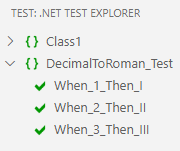

Step 1: Red phase, write a test.

Decimal 1 should return “I”.

Running the test is not possible at this moment, because the Romanizer class doesn’t exist yet and that means compilation errors.

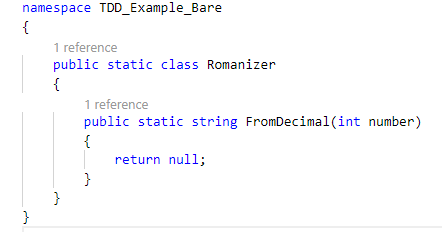

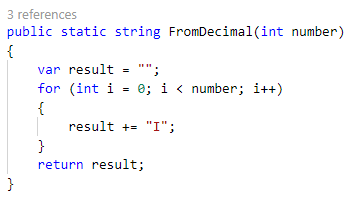

Step 2: Green phase, make the test pass

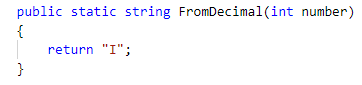

Add the Romanizer class and give it a FromDecimal method that takes an integer and returns a string. I like to make sure that the test still fails when the code compiles. That way I know I’m starting with a failing test as a result of assertions in the tests.

So I write an implementation that I’m sure will fail.

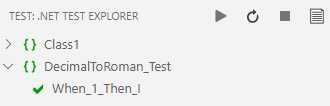

Now create the simplest implementation that’ll make the test pass.

Silly? No. The code is correct and it makes the test pass.

Coming up with an algorithm that might work is premature at this stage. You might get it right, but it’s more likely you won’t. And that can land you in very hot water (see further down.)

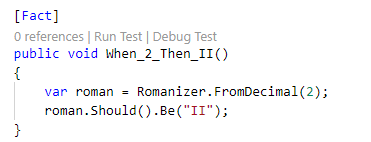

There isn’t much to refactor yet, so onto the next test.

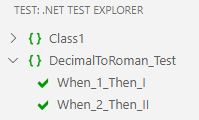

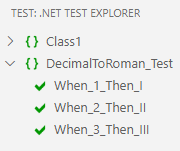

That if-else-if construct isn’t very elegant, but two cases don’t merit refactor yet, so on to the next test.

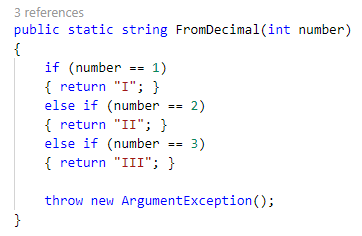

Yes, all green, so we can finally do something about that if-else-if construct, because 3 cases do merit a refactoring as the Rule of 3 now applies.

The pattern is clear. You need as many “I”s as the number that’s passed in.

Of course, knowing how Roman numerals work, the pattern won’t hold.

But breaking your brain on an algorithm in advance is not the way to go. You’ll likely end up tweaking it for every test you add. And getting grumpy when every tweak causes different tests to fail.

When you write the simplest code and refactor, you grow the algorithm as you go. A much better and easier way to do it.

When you refactor, you don’t do it haphazardly. But you follow a structured process to clean up the code.

You identify code smells and apply a specific refactoring to remove it. Martin Fowler wrote the book on how to do it: Refactoring: Improving the Design of Existing Code.

The purpose of refactoring is to improve the extensibility of your code by

-

improving readability

-

making it easier to make changes

-

reducing complexity

-

improving internal architecture (object model) and making that more expressive

What’s really important is that refactoring is what gets you clean, uncomplicated code that’s easy to understand, change, and test. And you’ve already read what that gets you.

In practice, the speculation phase is divided into two steps: the project initiation step and the adaptive planning step.

The project initiation step is the earliest phase in which the organization develops project management information, a mission statement for the project and initial requirements.

The adaptive planning step is the phase in which software components are assigned for being built or assembled. During this phase, the team executes the following steps:

Why Is Practicing TDD So Hard?

Practicing TDD is not a bed of roses. At least not at first. Here are the reasons why.

-

Because you have to think about what you want your code to accomplish, and how you’ll protect it against breaking (test it).

-

Because, it has a steep learning curve. You need to learn the principles and design patterns to create clean code and how to refactor to keep it that way.

-

Because code fights back. Existing code that’s not under test catches you between a rock and a hard place. You need to refactor it to bring it under test and you need tests to refactor it. I highly recommend Working effectively with Legacy Code by Michael C. Feathers for this.

-

Because you experience the costs of TDD immediately and the cost of not doing it much later. The lure of letting it slip is strong. You know you’ll pay the price when the bug reports start flooding in. But that’s later, isn’t it?

How Can You Fail at TDD—What Are the Common Mistakes?

-

Not following the test-first approach.

-

Not refactoring all the time.

-

Writing more than one test at a time.

-

Not running tests frequently, losing out on the early feedback from them.

-

Writing tests that are slow. The whole suite should complete in minutes or even seconds.

-

Using your unit tests to do integration testing. Nothing wrong with using your unit test framework to run integration tests. But integration tests are by nature slow, so you need to put them in their own test suite.

-

Writing tests without assertions.

-

Writing tests for trivial code, such as accessors and views without logic.

-

The original text on TDD: Test Driven Development, By Example by Kent Beck.

-

Working effectively with Legacy Code by Michael C. Feathers.

-

Refactoring: Improving the Design of Existing Code by Martin Fowler.

-

The Art of Unit Testing: With Examples in c# by Roy Osherove

-

Growing Object-Oriented Software, Guided by Tests by Steve Freeman

-

Clean Code: A Handbook of Agile Software Craftsmanship by Robert C. Martin (Uncle Bob)

-

The Clean Coder: A Code of Conduct for Professional Programmers by Robert C. Martin (Uncle Bob)

What Is the Difference Between TDD and BDD?

Behavior driven development and test driven development are similar and different at the same time.

-

Both employ test-first approaches, but are not about testing.

-

BDD is about improving collaboration and communication between developers, testers, and business professionals. To ensure software meets both business objectives and customer requirements.

-

TDD is about design and specifications at the code level.

-

BDD works at the application and requirements level. TDD focuses on the level of the code that implements those requirements.

-

TDD is, or can be used as the “Make tests pass” phase of BDD.

-

In TDD you can, but don’t need to, use techniques from BDD down to the smallest level of abstraction.

-

BDD doesn’t have a refactor phase like TDD.

Don’t Wait, Go After Your Bed of Roses

As you have seen, Test Driven Development is a simple technique to describe, but a lot harder to practice.

As with any skill, you’ll need to practice a lot to move it from your head into your bones. To make it second nature and get to the point where you’re developing faster with TDD than without it.

But, as you’ve also heard, the rewards are sweet, very sweet indeed.

Developing with confidence. Never dreading another release. Delivering value at a predictable sustainable pace.

A nice bed of roses! So, take the plunge. The sooner you start, the sooner you’ll get the practice in, and the sooner you’ll reap the benefits.

Check out Nimble Now!

Humanize Work. And be Nimble!