- Why Nimble?

- Products

_____________________

- Solutions

- Customers

- Resources

- Login

- Try Nimble for Free

- Why Nimble?

- Products

_____________________

- Solutions

- Customers

- Resources

- Login

- Try Nimble for Free

Navigate to

Hearing Truth as a Leader? You Must Be Jesting!

- 7 mins read

- By Carlos Schults

You think you know what’s going on.

You believe your perception of your company is an accurate measure of its temperature.

But your thermometer may be out of whack.

You welcome hearing your people’s truth. You need it. After all, how can you support them if you don’t know issues they’re facing?

But they will keep it from you.

Not to keep you in the dark. Not maliciously.

Au contraire, it’s just plain-old human nature.

It’s challenging, to put it mildly, for people to be themselves when their boss — a.k.a. you — is around. So they may say what they think you want to hear. And unfortunately, the result is that you get a distorted view of the state of your team or organization.

The common advice is to create psychological safety, to invite opinions and suggestions, and to respond without judgment or offering your 2 cents.

The uncommon advice is to do the royal thing.

To appoint a court jester. Or, if you like, a corporate jester.

Read on for a deep dive into the jester’s role, why you want one — or more! — and what challenges and pitfalls you need to be aware of.

Let’s start by examining why it’s so hard to hear the truth as a leader.

Why It’s So Difficult To Hear Truth as a Leader?

In what’s totally unsurprising news, people won’t be honest with their leaders out of fear.

Fear of repercussions for piping up and being honest in doing so.

There are rational and irrational components of that fear.

Boss = Saber-Toothed Tiger?!

Wouldn’t it make sense for honest, hard-working, smart employees that care about the good of their team and company to communicate with their leaders as honestly as possible way?

Absolutely.

But a disheartening fact about the human condition is that we aren’t nearly as rational as we think ourselves to be. In many circumstances, we act in quite irrational ways — and predictably so.

All of us – you and I, everyone around you, and even King Charles – have a brain that’s not adapted to the smartphones and office politics but to the environments of thousands of years ago, when resources were scarcer, and life was more dangerous.

Thus, our brain interprets many work situations through the lens of its life-and-death, fight-or-flight internal logic.

And interactions with the boss fall into the risky category.

Any faux pas can lead to being cut out of the loop. And that’s just the start.

Ultimately, it can cost you your job. In the not-too-distant past, it could quite literally cost you your head.

Messengers Were Shot

Of course, employees sometimes have perfectly valid reasons for not speaking up at work: they have witnessed — or worse, suffered — the consequences of doing so.

Unfortunately, not every organization has the organizational maturity that is necessary to foster a psychologically safe environment.

Also, there are many leaders out there that don’t really want to hear the truth, despite claiming to do so.

Thus, there are places where people are shamed and even ostracized after saying “the wrong thing.”

There are people who, instead of actively listening and acting upon critical feedback brought in good faith, punish bearers of unwelcome news. As kings of the past, they shoot the messenger. Though fortunately, they don’t do that literally anymore.

The fact that you’re reading this means you aren’t that kind of person. And you want everyone in your organization to feel free to speak up with welcome and unwelcome tidings.

Bringing back the jester of yore gets you to hear truth spoken and signal it’s safe to do so.

Jester to the Rescue!

Let’s start by quickly reviewing the role of the historical jester in medieval courts.

The Historical Jester

Wikipedia defines “jester” as “a member of the household of a nobleman or a monarch employed to entertain guests during the medieval and Renaissance eras.”

In medieval times, jesters enjoyed the “jester’s privilege,” i.e., they had to right to mock and talk freely without being punished.

Back in those days, jesters were the ones responsible for saying the hard but necessary truths and delivering bad news fearlessly, with humor and wit to soften the blows they dealt.

They said what everyone else thought but was afraid to say.

The Corporate Jester

A corporate jester is exactly modeled on the historical one: someone who has the right to talk freely and without repercussions. So the higher-ups hear what they need to hear, however uncomfortable, and can use it to find out about issues and opportunities for change and innovation.

Finding a corporate jester isn’t such an easy task, though.

You’d have to ensure this person is brave but kind.

A jester needs the courage to tell the truth, high levels of the perception to “read the room,” and the skills to say it with humor and wit, and with respect and compassion toward everyone in the organization.

Unlike the historical jester, the corporate jester doesn’t have to entertain and be funny. But a sense of humor helps with two things: relieving the tension of unwelcome news and making the message stick.

Answers to Your Most Pressing Questions About Having a Jester

Now that you know what a corporate jester is, let’s explore the role a little further with a series of questions.

Do I Need a Jester?

You might be wondering whether you really need a jester.

After all, shouldn’t you be trying to foster an environment where everyone is allowed to be honest, safely?

That’s a fair point.

You definitely want to encourage everyone to speak their truth by creating an environment that incentivizes people to do so.

But one does not preclude the other.

Even in a psychologically safe environment, it’s worth having someone with the explicit role to question the status quo — the established ways of doing things, and lay bare opportunities for change and growth.

Does It Need To Be a Real Position?

Should “corporate jester” be a real job on your payroll?

Most likely not.

It could work, but you could also risk having the uneasiness people feel around the boss be transferred to the jester. If people know that John Smith is THE corporate jester, they might feel intimidated by him, negating any benefits you’d get from the whole thing.

Making the corporate jester an unofficial, rotating role brings many benefits:

• No single person gets stigmatized as the jester (and what they say dismissed)

• You get to hear multiple points of view

• Multiple people get to practice being more open and honest, and can then continue with this habit, even after no longer being the jester

Depending on the size of your company, you can have jesters at different levels, from the C-suite, through middle management, all the way “down” to individual teams.

They’d use the “jester’s privilege” to point out the elephants in the room: what everyone is aware of, but doesn’t mention.

Where Does Having a Jester Leave My Role as a Leader?

Hearing truth, having people tell you their issues so you can address them, takes more than getting a jester.

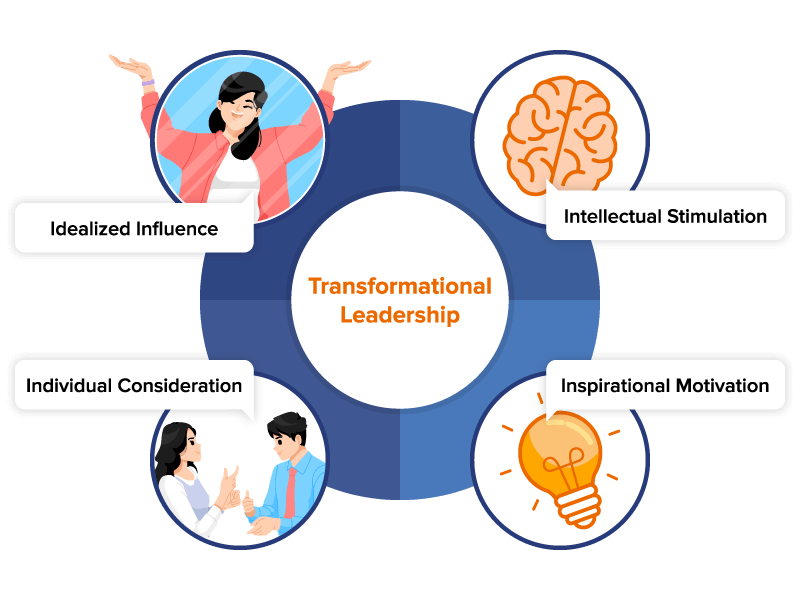

As a leader, your most important role is to be a role model in creating a culture of openness, trust, and honesty. This comes in several steps.

First of all, you need to understand the value and importance of honesty and truth.

Do your homework: read, study, use the resources at your disposal to learn how trust and honesty are important in fostering innovation and efficiency in a corporate setting.

The second step is to make it public. Explicitly let people in your organization know that:

• the organization values openness and honesty

• telling the truth is always the right thing to do, even and especially if it’s hard to do

• no one will be punished for being honest

The final, most important and hardest step is to live all of the above, to walk your talk, to model and exemplify how you want others to act.

That means that you:

• are honest and transparent at all times, even if it means being the bearer of bad news

• don’t punish people for their honesty, as long as they’re kind and respectful

• know how to listen and accept feedback, and act upon it when it’s warranted

• are compassionate and human, particularly when delivering not so great feedback

Won’t Jesters Create a Lot of Chaos?

Jesters are supposed to make pointed observations and question what happens and how things are done.

If you were to act immediately on everything a jester points out, that could indeed lead to chaos.

So, don’t do that.

Instead, listen. Ponder.

• What nuggets can you find in what a jester points out?

• What messages keep popping up, perhaps in different forms?

• What are the takeaways?

And then pick out the cherries — the amazing opportunities for growth and improvement that are in line with your organization’s objectives — and act on those.

Never Shoot the Messenger

No one likes to be the bearer of bad news.

But quite often bad tidings are the most crucial ones you should hear as a leader because there’s no way to address issues you don’t know about.

Getting yourself a corporate jester, or several of them, is an excellent addition for hearing truth to the common advice of creating psychological safety.

After all, you’ll hear even more about what’s really going on when everyone, not only the jesters, feels free to be open and honest.

Author: